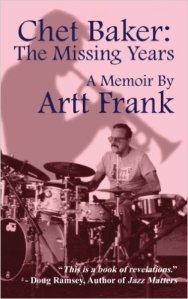

Chet Baker:

The Missing Years:

A Memoir by Artt Frank

**Book Blitz**

Today we feature Hall of Fame bop drumming legend, Artt Frank.

"top ten list of beautiful, romantic ballads that I personally like, and

Chet used to sing and play most of these also"

1- 'My Foolish Heart.

2- My Funny Valentine

3-This Is Always

4- Someone To Watch Over Me

5- Living For You (or, Easy Living)

6-Everything Happens To Me.

7-Bewitched, Bothered And Bewildered

8-O' You Crazy Moon

9-I'm Old Fashioned

Available on Amazon

Praise for Chet Baker: The Missing Years, A Memoir by Artt Frank

In August of 2012, jazz great Dave Brubeck gave the following review of Artt’s memoir:

“Artt Frank, the author of Chet Baker: The Missing Years is a devout Christian who practices what he preaches. His personal memoir of his meeting and subsequent friendship with the jazz genius of the trumpet is an unvarnished, honest portrayal of Chet Baker. In depicting Chet’s struggle to recovery, Artt reveals great compassion for a sensitive soul fighting for a life, and puts to rest the rumors and gossip that circulated about Chet’s ‘missing years.’”

– Dave Brubeck, Legendary Jazz Pianist and Composer

“About Chet a lot has been written, but alas, much of it is nonsense, repeating other nonsense. To get reliable information, we have to turn to the few people who actually knew him. Artt Frank not only knew Chet but kept in touch when it seems like the world had forgotten him; a period he calls 'the missing years,’ and rightfully so.''

Jeroen de Valk, author – Chet Baker: His Life and Music

“Chet Baker’s friend and drummer Artt Frank shows us sides of the great trumpeter that few people knew. In gripping detail, he tells of the well-known drama in Baker’s life—the sudden fame, the struggle with drugs, the effects of a beating that almost ended his career. But Artt gives us new insights into Chet’s warmth, his love of family, his steely determination and the early emergence of his astonishing talent. Frank’s photographic memory for conversations rivals Truman Capote’s. This is a book of revelations.”

– Doug Ramsey, Author of Jazz Matters and

– Take Five: The Public and Private Lives of Paul Desmond

“Chet Baker: The Missing Years is perhaps the most accurate account of Chet’s life and true spirit to date. Superbly written by Artt Frank ... the book gives fresh insight into the man behind the music. A must-read for everyone from the casual jazz fan to the serious student of jazz history.”

– JB Dyas, PhD, VP, Education and Curriculum

– Development, Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz

Artt Frank, bop drummer/composer, and author, is one of the few authentic bop musicians on the scene today. Born in the small paper mill town of Westbrook, Maine on March 9, 1933, Artt is best known for his long-term association with Chet Baker, with whom he collaborated for over 20 years. Artt has also been worked with an impressive list of jazz luminaries over the past sixty years including the great Charlie Parker, Tadd Dameron, Dexter Gordon, Sonny Stitt, Miles Davis, Bud Powell, Jimmy Heath, Al Cohn, Ted Curson, and many others, including one memorable night with the great singer, Billie Holiday

Artt Frank, bop drummer/composer, and author, is one of the few authentic bop musicians on the scene today. Born in the small paper mill town of Westbrook, Maine on March 9, 1933, Artt is best known for his long-term association with Chet Baker, with whom he collaborated for over 20 years. Artt has also been worked with an impressive list of jazz luminaries over the past sixty years including the great Charlie Parker, Tadd Dameron, Dexter Gordon, Sonny Stitt, Miles Davis, Bud Powell, Jimmy Heath, Al Cohn, Ted Curson, and many others, including one memorable night with the great singer, Billie Holiday

In 2004, Artt completed his book “Essentials for the Be Bop Drummer” with Pete Swan and published by Tim Schaffner, publisher (and drummer!) of Schaffner Press, Inc.

Artt Frank was inducted into the Oklahoma Jazz Hall of Fame in November, 2010.

He currently lives in Green Valley, Arizona with his wife, Lisa Frank.

To learn more about the author, visit: www.ArttFrank.com

AN EXCLUSIVE EXCERPT

Chapter 1 Our First Meeting

I met Chet Baker in March of 1954 in a Boston jazz club called, “Storyville.” But the first time I heard Chet’s music was over the Armed Forces radio aboard the USS Des Moines in ’53 toward the end of the Korean War. Listening to Chet’s trumpet on that radio, I cried inside, unable to understand how a trumpeter could affect a drummer so much. Right then, I sincerely sent up a prayer that I would get home safely and get a chance to meet and play with Chet Baker.

|

Since I was about six years old, I’d been playing drums on anything I could find. By the time I was in my teens, I tried to imitate the beats of my favorite drummer, Gene Krupa, on the tabletop at home in Westbrook, Maine. Still, the only other musician who had affected me the way Chet did, was when I first heard Charlie “Bird” Parker and the new form of jazz – Be Bop. At 17, I hitchhiked to New York City from Westbrook, just to hear Bird in person at The Royal Roost. And maybe get the courage to ask him if I could sit in. I did, and he and Max Roach were kind enough to let me play.

Now, at 21, the war was over, I was honorably discharged and home working at the paper mill, like my father and most everybody in Westbrook, and still in love with jazz and drumming.

Chet Baker had just won both the Downbeat and Metronome jazz magazine polls for America’s number one new jazz trumpeter. That night in ’54 when I got to Boston, the Storyville club was jam-packed. My first impression of him was not only was he gifted, but also he was a very handsome young man as evidenced by all the beautiful young girls surrounding him. I waited until most of the girls and fans left, then made my way over to the bandstand to say hello. I wanted to make him think we had met once before, so as I approached I extended my hand, and said, “Hi Chet, Art Frank. Remember me?”

He looked at me for what seemed an eternity, shook his head, and said, “No, no, I don’t remember you, man. Sorry.” He said it softly but directly. I learned right then and there that Chet was very quick, intent and painfully honest. He looked you in the eyes when he spoke. It seemed like he could pretty much read your thoughts on the spot. I got the feeling he’d tell you the truth even if it meant his losing a fan by doing so. Man, if Chet had been a gunfighter during the old Wild West days, he no doubt would have stared down Jesse James. That’s how intense he was. And conversely, he was quite approachable.

As I spoke, he studied me for another few seconds or so and asked when and where we were supposed to have met. Rather than continuing to lie, I confessed that I hadn’t really met him in person, but how terribly moved I’d been by his sound and the way he played when I’d first heard him on the radio aboard ship during the war. He smiled, obviously liking what I had said, and when he did, I couldn’t help notice that one of his upper front teeth was missing on the left side. I was about to ask him how he’d lost it when the bass player, Carson Smith came over and stopped my train of thought. Chet introduced us, and we shook hands briefly. Carson excused himself and walked off toward the bar area. Chet didn’t appear to be in any particular hurry to get rid of me, smiling and nodding at the beautiful young chicks as they walked by.

I went on to tell him about the prayer I’d made when I had first heard him play; that I’d be able to meet him one day, maybe even get the chance to play with him and his group. He studied me curiously and asked what instrument I played. I told him I was a drummer, and had sat in with Charlie Parker at the Royal Roost, and a lot of other great bop musicians along 52nd Street. Bop drummer Stan Levey had also given me a lot of inside tips on how to play. Chet seemed impressed and smiled warmly. As far as getting the chance to play with him one day, he said in his soft, melodic voice, “One never knows, man… one never knows.”

Carson and Russ were on their way outside and asked Chet if he wanted to go out for a breath of fresh air. He nodded, excused himself and left me standing there. Much to my surprise though, he stopped, turned half way around and gestured for me to join him. I couldn’t believe it. Here was Chet Baker inviting me to join him. Once outside the club, I lit up a cigarette and offered one to Chet. He just shook his head and told me he didn’t smoke. He stood by watching the traffic whiz by. He had the interest and intensity of a little boy on some long ago Christmas morning watching his father operate a set of Lionel trains on a miniature set of tracks on a worn out linoleum covered floor.

After a minute or so, Russ and Carson told him they were going back inside the club, but Chet was too focused on watching all the cars go by and didn’t respond. They left and I don’t think Chet even realized I was standing there beside him until a minute or so later. He turned around and asked me where Russ and Carson had gone. When I told him what happened, his face lit up with a smile. He told me that whenever he watched a lot of cars speeding by, it brought to his mind one of the few things he would most like to do in life -- drive a race car at Le Mans and win. “What a thrill that would be, man,” he said, a kind of daydream look in his eyes.

While I stood there listening to him, it occurred to me that I was talking to the nation’s number one trumpet player, and he’s telling me how he’d like to be a racecar driver. I told him he could probably do anything he set his mind to. Where I came from in Maine, racing cars against each other was what most of the young guys did every night and weekends for excitement. Hearing that brought another smile. He told me that most of the young cats in L.A. were doing the same thing. I guess it must have been pretty much the same way in every city and town across the country.

I asked him where he and his group were going after they left Boston. He said they would be doing back-to-back gigs in different cities before winding up doing a full month at “Birdland,” the world-renowned jazz club in New York City. The first two weeks of that gig he would play opposite sets with Dizzy Gillespie’s group, and the following two weeks, opposite sets with Miles Davis’ group. He was real excited about the prospect of that. He was gracious and told me that if I could make it down during one of those weeks, I’d more than likely get the chance to sit in with him. I was ecstatic when he said that, and told him I’d do my damnedest to make it down on one of the nights he’d be sharing the stand with Miles Davis. He said he hoped so, and I believe he genuinely meant it.

I knew he had other things to do, and I didn’t want to get off to a bad start by taking up any more of his time. He still had another set to play, and I had a hundred and five mile drive back to Westbrook, Maine. Also, I had to be at work at the paper mill by 6 a.m. the following morning. I worked the ‘swing shift.’ One week I’d work the 6 a.m. to 12 p.m. shift, the following week I’d work from 12 p.m. to 6 p.m., the next week I’d work from 6 p.m. to midnight, and finally, I’d work the graveyard shift, from midnight to 6 a.m. I hated the swing shift because it was very difficult to make plans to do anything. I really didn’t want to leave the club, but knew I had to. I shook Chet’s hand and told him I hoped to see him again when he played Birdland, and left the club reluctant, but elated.

Almost as soon as I had driven out of Boston, a mixture of snow and rain started to fall softly, causing the roads to be a bit slippery, not the least unusual in early spring. But I didn’t care. I was absolutely ecstatic because I had finally met and talked with my main inspiration in jazz, Chet Baker, and he’d been very warm toward me. I praised and thanked God for hearing my prayers about meeting Chet.

The snow continued to fall but it never really amounted to anything, at least until I hit Route 1 in Maine, where the road became even more slippery. I made it home just before 5:00am, about the time my father would be getting up. He had to get up at that time each morning to get the wood stove fire going so he could make his ‘Eight O’Clock’ brand coffee. He’d have to do this in the spring, summer, fall and winter because we only had one wood-burning stove in the house and that was in the kitchen. Whenever I’d get home late, as I did in this case, I’d come upstairs very quietly so I wouldn’t awaken him. But lo and behold, there he was, already up, dressed and sitting at the table waiting for the coffee to finish perking.

It seemed that every winter morning in Maine was a particularly cold one, and this March morning was no different. My father busied himself putting pieces of wood into the stove in order to have it warm for my mother and the other kids who’d soon be getting up. I swear, every other room in that apartment was freezing and the floors were as cold as glaciers. There was absolutely no insulation or storm windows, no central heating system nor even running hot water. In order to have hot water, we would have to fill a pan with water and heat it on the front of the stove.

This was a routine my father did each and every morning before he would sit down and enjoy his cup of coffee - after which, he’d put on his light weight frock coat, a railroad cap, leave the house and go out into the freezing cold. Not having a car, he’d walk the mile and a half through deep snow to get to work at the local paper mill. But God bless his heart, he was happy for me when I told him about the whole episode of meeting Chet. My dad played a C Melody sax, which is comparable to a soprano saxophone, but he never really got the opportunity to play in any of the nightclubs in nearby Portland. He was too busy working seven days of every week to support seven of us kids.

While we sat there talking, my mother woke up and joined us. Still being excited, I went over the whole story again, filling in each and every little detail, and later the same day, I relived it again with my three brothers and three sisters. I know it sounds crazy, but that’s how important it was for me to have met Chet Baker.

My mother, having a ‘steel trap’ memory, recalled how I’d bought a record by Chet the year before, the day after my discharge, and wanted me to play it. I got the turntable from my room and played it for them. Hell, all I did for weeks and weeks was play The Lamp is Low on that Chet Baker record until I nearly wore the grooves out. There was something in Chet’s music that got to me. I was so excited about the possibility of seeing Chet again that I wanted to share his music with everybody. I’d open the windows and play his record so the neighbors next door would be able to hear the sounds too. Some of them didn’t mind. But there were a few others who always squawked. They were too square, but I played the records anyway!

As luck would have it though, when it came time for Chet and his quartet to begin his month at Birdland, I was working the top part of the swing shift, 6 a.m. to 12 pm - which meant that by the time it came around for Chet to be playing his two weeks opposite Miles Davis, I’d be working the 6 p.m. to midnight the first week and the midnight to 6 a.m. shift the second week. Unless I could find someone to swap shifts, I’d not only miss the chance to see Chet again, but also miss the chance to sit in and play with him and his group. To say that I was frantic would be an understatement. I called the other two guys who worked the swing shift, and asked each one if they’d be willing to swap their shifts with me for the last two weeks of the month, but unfortunately for me, they could not for each had made plans of their own. So that March night of 1954 in Boston turned out to be the last time I would see Chet for the next fourteen years.

# # #

No comments:

Post a Comment